|

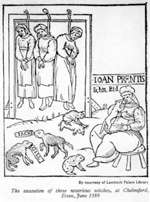

Witchcraft Cases - Elizabeth Lowys, 1565 & Joan Prentice, 1589 In 1563 Elizabeth I's government passed an 'Act against Conjurations, Enchantments and Witchcrafts,' which opened the way for a period of persecution that affected England for the rest of the sixteenth and well into the seventeenth century. Now a felony, the 'crime' of witchcraft could be prosecuted in local courts. One of the first persons to be dealt with under this new statute was Elizabeth Lowys from the Essex village of Great Waltham.58 The illustration shown here is of another Essex case, that against Joan Prentice of Sible Hedingham. The Prentice Case has been aired in Essex recently.59 The Latin indictment is preserved in the nation's archive, the Public Record Office.60 It is stark and follows the usual highly formalised language of indictments. The 'facts' are given. On 10 February 1589, Sarah Glascock, a two year old was bewitched and languished six weeks, afterwards dying on 27 March. This was attributed to the evil power of Joan Prentis, 'fascinatrix incatratix'.. There are endorsements at the foot of the document, 'billa vera', or a true bill. Included in some scrawl by the scribe is po se cul ca cull indm. Joan Prentis 'placed herself on jury for good or ill'...'she has no chattels'...and 'she is hung by the neck at Chelmsford Assizes'. There is another source, a pamphlet printed for a London readership, from which the illustrated title page comes. The status of this document is not so clear. It bears some of the hallmarks of an interrogation by a Justice of the Peace, perhaps conducted in Colchester Gaol, where Prentice had been taken under suspicion. But it is not certain what editorial process has occurred and how much has been invented for a popular audience. It is an oddity. Why is the ferret necessary? A compact or link with the Devil was essential for the legal niceties, as much as for the religious beliefs of the time. There was no mysterious power in the witch. Her 'skill' came less from her own hand or from sorcery picked up from a book but via the 'animal'. 'Familiar' was the language of contemporaries for this phenomenon of ambassadors of the Devil. Elizabeth Francis in 1566 had a white cat. Kemp had two cats. The two black frogs in the picture, Jack and Jill, were the companions of Joan Cunny who hanged with Prentis. There is a folk-loric element to these cases. George Gifford an early commentator on witchcraft wrestled with this puzzle as to why such servile lesser agencies were used as these imps. Why would the 'Rulers of the darkness take upon them the shapes of such paltry vermin as Cats, Wise Toads, and Weasels'.61 They were in evidence in so many cases in Essex and required explanation. The answer was believed to lie in subtlety. They appeared as mean and trivial creatures to cover and hide their mightiness! There appear to be many more cases of witchcraft outstanding in Essex than elsewhere in the country.62 Rather than search for an explanation in the supposed nature of Essex people, (a supposed reluctance to abandon old religions and customs), a likelier cause seems to be that the relevant papers survive soonest here than elsewhere. While it is one of the five English counties to have C16th Assize records, it surpasses the other four in starting in 1556, some 33 years before any other.63 A settled history in Essex's proximity to London, compared with say the more turbulent border marches , coupled with the accidence of survival and an accessible record office may be more significant than the theoretical characteristics of 'Essex girls'. But quite why women and older women at that should form 90% of those accused in Essex still teases us, as it teased Divines of an earlier age. There were convenient myths and Biblical explanations to hand. Ever since Eve, women were regarded by men as soonest to become involved with the Devil's illusions. James VI of Scotland in his Demonologie,(1597), saw women as frailer and easier to entrap. The misogyny of the age gave credence to such views. A concern with witchcraft did not spring newly into being in England. There is an earlier and European context. Helped by the invention of printing, the witch-hunting craze picked up pace with notorious theoretical work like Malleus Maleficarum, the' Hammer of the Witche's, (1487), by the Dominican inquisitors Institoris and Sprenger A Papal Bull of 1481 gave official endorsement to this misguided zeal. In Lorraine in the 1580s, for example, the judge and demonologist Nicholas Remy claimed to have burnt 900 witches.64 The relationship between periods of economic and civil misery has long been noted. Voltaire's was the original historical perception of the historical phenomenon. There was a second great flowering of witch-hunting in Essex occurs during the un-settled period of the Civil War and Commonwealth and in the misguided labours of Matthew Hopkins of Manningtree. The world of witches is not merely the preserve of students of folk-lore. Witchcraft beliefs formed an important part of the rich popular culture of early modern Europe.65

|

||||||||

|